They don’t mean to make it obvious. They are contorting their faces in an attempt to convey understanding, they are making sad cooing noises, they are apologising. Maybe they are reaching out and touching my arm, but they cannot hide it. What most women want to tell me, and some often do, is that I am living their worst nightmare.

Daughter Widow.

Since my mum died, I have been voracious in my search for essays, articles, poems, anything written and recorded and true that I can relate back to my own experience. I search ‘dead mum’ ‘motherless daughter’ ‘mum dead addiction grief’ ‘estranged mum dead’ on Google, Substack, Good Reads, Letterboxd. I ask for suggestions. I want a still body of water in which to see myself reflected in. I want to wade waist deep into it. I want to be understood.

I often turn up empty handed, disappointed.

Maybe Daughter Widow is an offensive term, for which I can only apologise, but I think it sounds good. I think it feels appropriate.

I am a Bad Daughter Widow for a number of reasons which include, but are not limited to:

I make jokes about my Dead Mum all the time. Sometimes I allude to her being in hell.

I was able to read my Dead Mum’s eulogy without crying.

I do not, technically, miss my Dead Mum.

I was deeply unkind to my Dead Mum the last time I saw her, and many times, spanning across many years, before that. I felt entitled to this cruelty.

I was estranged from my Dead Mum when she died.

My grief is not about the Dying. Not necessarily.

Good Daughter widows are girls (no matter what age) who mourn their Dead Mums in beautiful, heart-wrenching ways. They tear up as they try on wedding dresses wishing she was there. They write Instagram posts to her on her birthday and they think of her on Christmas. They look in the mirror and delight at the version of her they find there. They name their daughters after her. Their mums are Dead for Good Reason. Their Dead Mums put up Good Fights.

Those women that flinch and twist their faces when I tell them aren’t doing so just because I have a Dead Mum, just because I am a Daughter Widow - but often because of the intricacies of these facts, the nuances.

It was hard for most people to grasp why I felt the way I did when my mum died. As if my hatred for her cancelled out the love. As if the inevitability of a lifetime of alcoholism and drug addiction coming to an end in this fashion should have hardened me ahead of time. If I did not like her, then I could not love her, and if I did not love her, was I really grieving at all? My grief - its asymmetry and its impossible edges, limited their sympathies. This is not their fault, but still it made me petulant, drove a desire within me to isolate - both physically and emotionally. I relied upon minimising what I felt, holding it close to my chest like a flame I couldn’t give to the wind.

In reality, the grief I felt was brand new and white hot and utterly indecipherable. My new Dead Mum had no real, material affect on the life I was living. Unlike Good Daughter Widows, I did not find myself suddenly cut adrift. I did not wake that day, in the new fact of things, suddenly without text messages or phone calls or coffee dates, having to reshape my existence. The day before and after my mum died were more or less indistinguishable. So what was I wailing for? Where did the ache come from?

Sometimes I feel as though there is something inside of me that is wrong, cursed, and utterly contagious. This feeling is compounded when other women bare witness to the fact I am a Bad Daughter Widow, a feral thing. I can see that to them, to be motherless through death is one thing, but to have existed a long time in that state beforehand is unthinkable. How did I become myself? What sunlight did I grow toward? Nobody wants to admit it, but being a Daughter Widow is being a wrong woman. You earn that correctness back by being the Good kind. If only I could say: here is a Pandora charm my Dead Mum got me when I was younger. Here is a photo of the two of us at dinner, prosecco in hand. Here’s the two of us last Christmas. Here we are, loving each other.

What I have by means of keepsakes of my Dead Mum

Letters she wrote from the rehab facility (see: nunnery) that she went to twice, in which she writes about feeling good, about what she’s been doing (see: praying, developing a superiority complex among the other women), and asks me for things (puzzles, word searches, books, non-prescription glasses);

One email in which she drunkenly professes to be sober and implores I forgive her, and

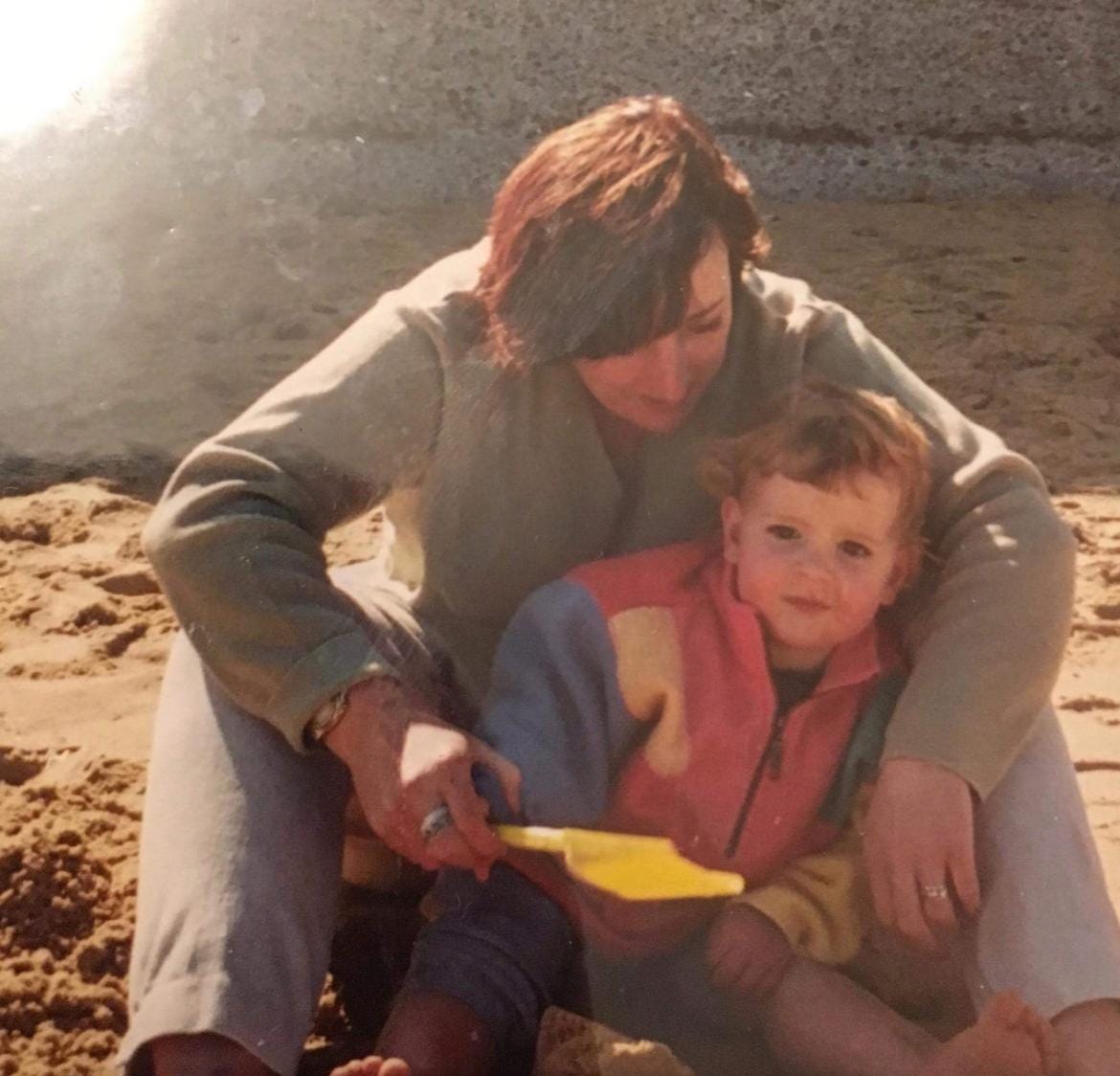

Photo albums, lots of them, that date until around 2005, and then stop. They feature mostly photos of myself and my siblings together, and as time goes on, fewer and fewer of us alongside her.

In all of my digging and searching and excavating of various resources I have yet to find much in the way of media that I feel truly spoken to by. It is not the responsibility of any artist to speak to me, to curate their craft in order for it to resonate with my own experiences. But still, it feels lonely sometimes. I read Annie Ernaux’s ‘I Remain In Darkness’ earlier this year which felt spectacular and uncomfortable, and listen a great deal to Runs In The Family by Amanda Palmer when I am feeling particularly self-indulgent. But perhaps the single most pertinent piece of media remains episode six of season five of BoJack Horseman - Free Churro.

For twenty or so minutes, BoJack reads the eulogy for his mother. A distant, neglectful, cruel woman. I was floored the first time I watched it, and changed forever, by the following line and its sentiments:

It is easy enough to follow - the idea that one’s life would be worse following their mother’s death. But the full quote is My mother is dead, and everything is worse now, because now I know I will never have a mother who looks at me from across a room and says, “BoJack Horseman, I see you.”

I did not envision that of all the ways I’d find to translate my grief, Netflix Sitcom about a washed-up actor and drug addicted talking horse BoJack Horseman would be the means with which I did so. But watching it for the first time opened up a linguistic faculty within me had been locked up by the logic of death, the duration of absence, by fact and reason, the responsibility I felt toward being pragmatic.

I am a Bad Daughter Widow because I am not sad my mum is dead. In fact I am reasonably pleased about this for her sake, for my sake, for the sake of my immediate family and the weight that was lifted in her passing. I am a Bad Daughter Widow because my grief is for what her being alive enabled me to imagine. Her living meant I could craft impossible and detailed futures in which not only was she clean and sober, but remorseful, present, entirely transformed. In one version, she holds my daughter. In another, we go for lunch with my sister. When my mum died, she took away my imagination. She robbed me of my ability to believe in a future where she says sorry. Where she tells me she loves me.

I am a Bad Daughter Widow because my grief is selfish. I am a Bad Daughter Widow because I am sad that my Dead Mum never got to play the role I created for her years down the line. I am a Bad Daughter Widow because I don’t miss who she was, but the possibility of her being who I wanted her to be. I am writing this because I am not the only Bad Daughter Widow. I am writing this for the other women who want the sinew and the splintered bone of it all. For the other Bad Daughter Widows, elbow deep in the dirt in the middle of the night.

I watched that episode of BoJack Horseman just last week and it deeply impacted me, and I am not even a widow son. It was haunting and disconcerting and still is. This piece is also uncomfortable and cutting and beautiful. Like the episode, it resonates in ways that aren’t necessarily explicit — someone recognizing their own mortality in relation to a person-now-made-concept, I mean goddamn.. it really hits hard. Thank you for sharing this.

I find myself constantly invalidating my feelings, trauma, and experiences because of this overwhelming guilt- how can I say I hate my mother when she is, well, my mother? Don't I have an obligation to love her? I write this as she is in the room with me.

"Her living meant I could craft impossible and detailed futures in which not only was she clean and sober, but remorseful, present, entirely transformed. In one version, she holds my daughter. In another, we go for lunch with my sister." And I juggle wanting all of it and none of it at the same time.